The Economics of Extremes

Economics has always been a dry and difficult subject for me—one I have struggled with constantly. Those who manage to make it simple and engaging, or even turn it into a thriller, certainly deserve gratitude. This book receives exactly such an acknowledgment from me.

The author argues that the world exists between two extremes. If we understand these extremes, understanding the future of the world becomes easier. He identifies nine such extremes across the globe, travels to these places, studies them closely, and presents his report.

Part One: The Economics of Survival

1. Aceh (ACEH), Indonesia

Aceh is an autonomous province of Indonesia whose history is shaped by Arab, Chinese, European, and Hindu influences. It was devastated so completely by a tsunami that even the shape of the Earth reportedly changed—the planet became slightly more spherical, and days grew shorter worldwide. Except for one mosque and a few elevated areas, almost nothing survived.

Yet after this massive destruction, the province’s GDP began to strengthen. How?

The author reveals a strange and unsettling theory:

“Natural disasters can act as catalysts for economic growth.”

Reconstruction begins rapidly, new jobs emerge, foreign funding flows in, and the economy starts to boom. Another factor is that the people of Aceh have, for centuries, placed immense value on gold. Everything was lost—homes, families, jobs, and even the value of currency—but buried or smuggled gold survived.

2. Zaatari, Jordan

Zaatari is the fastest-growing refugee camp in the world, home to refugees from Syria. These people have lost everything and survive on United Nations aid. Yet the employment rate here is higher than that of France, and the camp’s total income exceeds 14 million dollars. How?

The author offers a striking example:

“We go to supermarkets with money, buy what we need, and return with empty pockets. In Zaatari, people go to supermarkets with empty pockets, buy what they do not need, and return with full pockets.”

The UN loads money onto cards meant for ration purchases. Refugees buy canned goods instead of essentials and sell them illegally on the black market to Jordanians. Meanwhile, teenage family members secretly cross into Syria, bring back cheap goods, and sell them locally. Thus, a thriving illegal economy emerges with virtually zero capital.

3. Louisiana State Prison, USA

One of the most notorious prisons in the United States, Louisiana State Prison is a place where those who enter rarely leave. Dollar bills are banned. Outside goods are prohibited. And yet, a complete trading system flourishes inside. Anything can be obtained. How?

The mechanism is not difficult to understand. Guards are bribed. Cigarettes are commonly used as currency in American prisons—but here, even cigarettes are banned. So inmates invent an invisible currency. What is money, after all? A promissory note?

Here, a single dot drawn on paper becomes currency.

Part Two: The Economics of Destruction

To understand the economics of destruction, one only needs to look at a decaying Indian palace—its elephant sculptures broken, their trunks missing, replaced by creeping vines. Immense prosperity is like a majestic elephant, difficult to sustain.

The author chooses three locations for this journey.

1. The Darién Gap, Panama

Beneath this dense rainforest lies the gold that once drew Christopher Columbus. This could have been one of the richest places on Earth. Yet today, the grand highway connecting North and South America breaks at exactly one point—the Darién Gap. There are no paved roads, no industries, and no settlers of the New World. Why?

First, Colombian guerrilla rebels hide in these jungles, comparable to Indian Naxalites. Second, the region is protected for indigenous tribes, isolated from the modern world. Third, this route facilitates illegal trafficking—from timber smuggling to human trafficking.

The author encounters six Sikh men from Punjab crossing these swamps, chasing the American Dream. They are robbed and cheated, yet they remain convinced that once they enter America, they will someday bring their wives and children from their villages.

2. Kinshasa, Zaire / Congo

This land holds diamond mines. Seventy percent of the cobalt used in everything from mobile phone batteries to Tesla cars comes from here. Its rivers and rainforests are extraordinary. This should be one of the richest countries in the world—yet it is among the poorest. Why?

The first reason is corruption—bribes are required for everything, even to pay taxes. The second is misgovernance under a dictator who imported barbers from New York while children starved. The third is relentless European exploitation, which continues today.

A brutal irony persists: while people buy electric cars to protect the environment, underage children in Congo mine cobalt for those very batteries.

3. Glasgow, Scotland

After reading the Booker Prize–winning novel Shuggie Bain, the truth of this city becomes clear. Once the world’s most prosperous and modern city, home to scientists like James Watt and Kelvin, it was the heart of the Industrial Revolution. Ships built here helped conquer the world.

Yet in the twentieth century, Glasgow declined faster than any other British city. Why?

First, it failed to adapt. Japan began producing cheaper and better ships, and markets shifted. Second, widespread addiction to alcohol and tobacco destroyed productivity. Third, administrative failures followed one another relentlessly. A city where doors once remained unlocked became a hub of theft and crime.

Part Three: The Economics of the Future

Are prosperity, better health, and technological advancement the keys to the new world? Is this the best possible path? Is this our future?

Richard Davies’ next journey takes him to three such places.

1. Akita, Japan

Readers of Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus may recognize the idea of human immortality. But can a world function where people simply do not die?

In Akita, one-third of the population is over 65, many over 100. Elderly people dominate public spaces. People in their forties and fifties are considered “young” and often denied entry to senior clubs. Football teams exist for those over seventy, dance clubs for those over seventy-five.

The problem is the absence of children. Schools are shutting down. Working professionals resent that they earn while the elderly enjoy benefits. In the past two decades alone, several derogatory Japanese terms for the elderly have emerged. Many seniors now keep robots for companionship—even robotic dogs. Young people in Akita wait, bitterly, for the old to die.

2. Tallinn, Estonia

Tallinn represents the world’s first fully digital state. Except for marriage, divorce, and land purchase, no task requires physical presence. Everything is automated and linked to citizen ID cards.

Remarkably, this small post-Soviet nation has become a technological powerhouse. Programs like Skype originated here, and children learn computer coding in primary school. They have even developed a “Click & Grow” machine for home farming, capable of growing multiple plants while automatically managing water and nutrients.

The author raises a concern: if machines do everything and humans merely operate them like video games, is this truly good? Estonia, he writes, is a global laboratory. If its digital bubble bursts, the world will learn. If it succeeds, all the better.

Read this also: Learning from America’s Indomitable Will to Live

3. Santiago, Chile

This case closely mirrors India’s future. Chile is South America’s fastest-growing “developed” nation, with a per capita income of 14,000 dollars—the highest in the region. Yet most of this wealth is controlled by less than ten percent of the population.

It is one of the most unequal developed economies in the world. A small elite holds immense wealth, a large population remains poor, and an equally large middle class sustains the nation through steady labor.

Years ago, the United States launched an exchange program sending Chilean students to Chicago for two years. These “Chicago Boys” returned, reshaped Chile’s economy along American lines, and became its wealthiest capitalists. Economic power remained within their families.

The author writes:

“As you travel by metro, income levels decline with each station. School and college quality deteriorates. Neighborhood names alone reveal wealth or poverty. Children from affluent areas secure top jobs with high scores, while those from poorer districts cannot even enter elite schools. Slowly, an Educational Apartheid has taken root in this developed nation.”

Conclusion

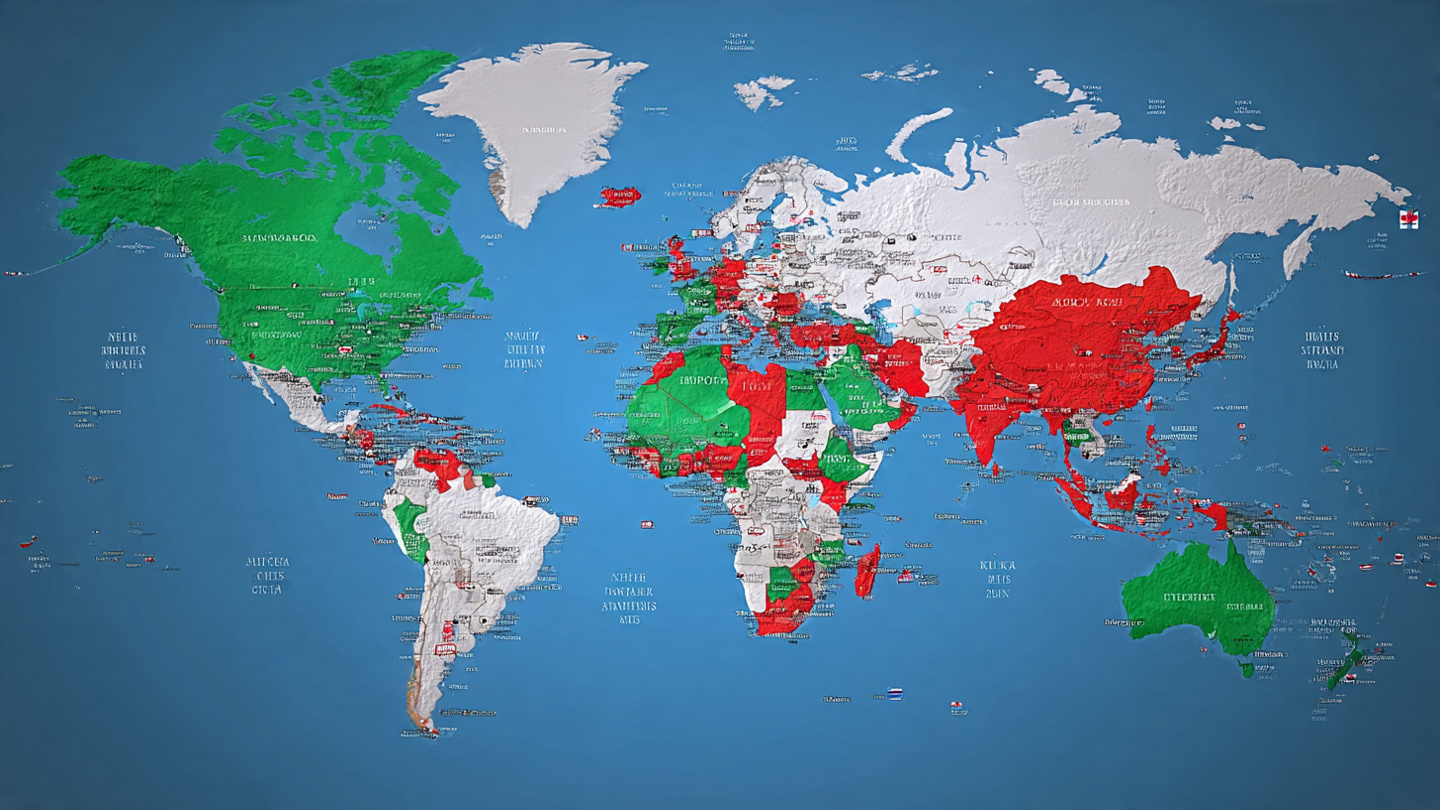

Through the nine locations described across these three sections, a global economic map emerges. The boundaries between prosperity and collapse become visible. Some limits can be crossed; others must be avoided.

(This book review by Praveen Kumar Jha was published in 2022.)

External Link: https://ig.ft.com/sites/business-book-award/books/2019/longlist/extreme-economies-by-richard-davies/

प्रवीण कुमार झा कथेतर रुचि के लेखक हैं। गिरमिटिया इतिहास पर उनकी शोधपरक पुस्तक ‘कुली लाइंस’ चर्चित रही। संगीत इतिहास पर आधारित पुस्तक ‘वाह उस्ताद’ को कलिंग लिट्रेचर फ़ेस्टिवल 2021 ने ‘बुक ऑफ द यर’ से सम्मानित किया। उन्होंने इतिहास पुस्तकों के अतिरिक्त लघु यात्रा-संस्मरण भी लिखे हैं और उनके स्तंभ प्रमुख पत्रिकाओं में प्रकाशित होते रहे हैं। प्रवीण का जन्म बिहार में हुआ और वह भारत के भिन्न-भिन्न स्थानों से गुजरते हुए अमेरिका और यूरोप में रहे। वह सम्प्रति नॉर्वे में विशेषज्ञ चिकित्सक हैं।

Praveen Kumar Jha is a writer of non-fiction. His research-based book on Girmitiya history, Kuli Lines, has received wide recognition. His book on music history, Wah Ustad, was honored as Book of the Year at the Kalinga Literature Festival 2021.

In addition to history books, he has also written short travel memoirs, and his columns have been published in leading magazines. Praveen was born in Bihar and has lived in various parts of India before spending time in the United States and Europe. He is currently working as a specialist physician in Norway.

Leave a Reply